Writing

The Trial of California’s Missions

Spring 2019; Avery Review, issue 41.

Excerpted, full text available here.

Missions on Trial

As monuments, missions preserve California’s Spanish colonial past and embody false ideas of racial superiority. Is the verdict then to execute them, as Ines Weizman would propose? Or to abandon the Mission Model Project? Or, perhaps, leave the missions to fall into their own ruin in exile? The legacy and aesthetics of the California missions is too entrenched in popular vernacular to be abandoned. Instead, an iconoclasm can be produced through critical modeling practices and artistic interventions of the site.

Missions are already preserved outside of their structure and within the cultural identity of California. Their aesthetic legacies are embedded in Taco Bell logos and in the Stanford University campus. Throughout the state and country, the syncretism of California Mission Style has further bastardized itself. The tectonic heft of the mission walls, which often span a thickness of four feet or greater, is superficially reproduced as wood-framed and gypsum walls sprayed with stucco. As with the sugar cube and foam-core models, these abstractions are significant. The heft is comprised of hundreds of handmade adobe bricks produced by indigenous laborers forced to work in inhumane conditions. The heavy, indelicate ornaments framing walls and windows reveal that the fabricators were not skilled European craftsmen, but indigenous people producing simulacra of the missionaries’ recollections of Spanish landscapes.[i] California mission style is necessarily a de-refinement.

But it is not just their style that is reproduced and preserved. Though the HABS documents end at the property lines established in the 1930s, the missions were connected rhizomatically through a network of agricultural landscapes. One mission could own hundreds of acres and thousands of indigenous people to work the land. The systems enacted in this landscape have continued to spread. Brown people continue to work the fields and their social positions have not improved. Farm labor and migratory laws continue to devalorize and dehumanize people. The missions draw no parallels or connections from their histories to current conditions. In fact, they monumentalize ideas of a kindly padre and his docile brown workforce. This settler-colonial mentality continues through the rhetoric and treatment of Central-American workforces.

Unlike other monuments, missions cannot be scurried away to museum storage spaces, where embarrassing colonial histories can be preserved out of sight. And ironically, the few that do attack the pedagogy inherent in mission preservation aim not at the building itself, but the statues around it.[ii] The vandals (artists? critics?) who perpetrated these acts repeatedly opted to let the architecture be. Jorge Otero-Pailos argues that, “Architecture is saved from obsolescence and appears contemporary as it is framed and reframed by preservation as culturally significant.”[iii] As the statues are newer entries, they are not viewed as part of what is culturally significant-- even a vandal will make that distinction.

A true iconoclasm of the missions fundamentally requires a reckoning with the building and the program it houses. If we are to examine and argue about its cultural significance then it is not enough to execute the missions-- history has shown us that this only serves to martyrize buildings.[iv]It is also not enough to exile the missions-- ruin seems to only make them more romantic. Artistic interventions and critical models should address and challenge the structure. Social and local networks, like the Catholic Church, the Mission Preservation Foundation, and elected community officials, should embrace a re-appropriation of the missions and the modeling project. If California’s missions can be appropriated to benefit colonial history, they can also be used to challenge that history.

The stakes are clear—California’s brown communities continue to be disenfranchised by a history that suppresses their role. Instead of preserving the constructed mission histories and superficially addressing concerns about brown bodies and narratives, missions should invite criticism and revisionism. Their programs should be reconfigured to help elevate the communities they have alienated. The drawings and models, which dehumanized these spaces, should now be re-examined by artists and students in order to find and produce proper representation. The state’s pedagogy should address the contemporary conditions the missions produce, instead of historicizing and abstracting negative conditions.[v]The missions continue to be central sites in California, so they must participate as true community spaces and cultural centers, not static, crystalized museums. Their walls should not be treated and reproduced as boundaries of exclusion, guarding an unknown value. Rather, they should be permeable membranes, in flux and relation to the people. Students and artists alike should be empowered to engage with the buildings, find their faults, find their beauty, and determine whether they are guilty or innocent. In order to move forward, the buildings must be held accountable.

Writing

Chicago Works? Curating Value and Representation in Chicago, Amanda Williams at the MCA

Fall 2017, Critical Terms in Modern Architecture,

Prof. Shiben Banerji

First Place Winner, Avery Review Essay Contest.

Excerpted, full text published here.

Corbusier describes cities as a “grip of man upon nature.”5 In his words we read the legacy of modernism as white male colonial practices rendered onto the bodies of black women—both nature and the black female body need to be forcefully controlled. This legacy is perpetuated and preserved in the multiple forms taken by white male privilege today. bell hook’s exegesis on feminism, Ain’t I a Woman?, expands on the grip of white man upon nature and the black female body. It stems, hooks argues, from an anti-woman mythology that allows an identity based on negative stereotypes to be thrust upon black women. Furthermore, she argues, white male power comes from the ability to use and capitalize on technological force.6 This brings us back to Roy’s invocation of “racial terror” and the “technologies of modern urban planning.” What is made evident is that the privilege accumulated across centuries has become institutionalized and writ large onto our modern domestic lives.

[Amanda]Williams renders this heritage visible in the angst of the lonely, chromatic houses of her Color(ed) Theory series, which forms a major part of the Chicago Works exhibition. Knowing the urban planning failures, lack of economic equity, and lack of social capital that gave rise to the houses’ impending demolition, we can read Color(ed) Theory as a bold response to the exploitation of the black home, which is, in turn, a metaphor for the exploitation of the black female. That the first works in Color(ed) Theory are painted to match and then titled after black beauty products is notable. Williams describes the process for finding the colors of Englewood identity as a casual brainstorm with her friends, in which she threw out colors and they responded “yes” or “no.”7 The colors register immediately in the neighborhood, where a discarded package of Newports might sit next to a crumbling Newport-green home, slated for demolition. With this shared palette, the neighborly collaboration of every house painting was a local and ephemeral act of reclamation. Captured in the museum as a series of photographs and short films, however, they become neatly packaged and summarized events. The audience is given enough to acknowledge the content but not enough to understand the context.

Gold is alluringly portrayed in several ways throughout the exhibition—positioned in the center like an open treasure chest or glimmering from behind a corner, just out of reach. The accompanying text acknowledges the value of this color, describing “material values and abstract notions of success” as well as ideas of “gaudiness and excess.” However, after having attended several of Williams’ lectures, it seems like the gold used in her work can mean so much more. A piece like It’s a Gold Mine/Is the Gold Mine? feels so much richer for the urban context from which its material was drawn (the bricks of demolished Chicago houses). But a site-specific piece built for the museum setting, like the gold-drenched room called A Dream or Substance, a Beamer, a Necklace or Freedom? looks contrived—so much so that it seems a little less brilliant under the pale-blue lighting of the awkward room surrounding it. Presented in the level field of the gallery, the two gold-covered pieces read as equally valuable, with the salvaged brick reduced to the same level of meaning as the new drywall.

Notes

5 Le Corbusier, The City of Tomorrow and Its Planning (New York: Dover, 1987), xxi.

6 bell hooks, Ain’t I a Woman? (New York: Routledge, 2015), 86.

7 “Amanda Williams in Conversation with Deanna Haggag,” talk, MCA Chicago, October 17, 2017.

Writing

Mad About You:

Peter Saul vs. America

Spring 2018

Methods in Contemporary Art History,

Prof.Mechtild Widrich

Excerpted from an essay. Please contact for full text.

One of Saul’s signatures is his incendiary treatment of the American psyche. He gladly rakes beloved public figures through the coals. Initially the title of Pop Art was thrust upon his body of work . Though he staunchly defied the reserved treatment many Pop Artists used of their subject matter. Richard Shiff, in quoting Saul, reveals this fascination with increasingly lurid imagery:

“I decided to maintain the direction of my pictures. I tried to increase the psychological impact, put more unusual characters in the electric chair”… Saul’s retrospective statement may seem flippant. Yet it conveys a blunt truth: he came to regard his well-developed drawing and painting techniques as enabling what was far more important for him—the viewer’s engagement with the subject matter.

Saul enjoys the role of enfant terrible.13 But, for Saul, the key is not in critical dissection, but social reception. The audience is lured in with a basal interest in phalluses, breasts, and an appealingly vivid smorgasbord of body parts and colors. Upon close inspection of the 1969 painting “The Government of California”, the audience might, perhaps, identify the disembodied head of Martin Luther King Jr. alongside Ronald Reagan and stop there. But the interwoven nature of the work prompts the viewer to trace the web. The tentacle labeled “honest” extending from King’s head gingerly clutches a Bank of America which is being pried open by a wrench clutched in another of King’s tentacles. Coins roll out and into the tentacle labeled “poor”. Yet another tentacle, this one labeled “clean” dusts the erect penis of Ronald Reagan with “syphilis”. Over the Golden Gate Bridge hang a series of toilet paper banners.

As the initial shock of the imagery washes away, we must make sense of what we see. Each element deftly weaves into another element. The caricatured figures force us to acknowledge the politically charged conversation of race in America. The tentacled figure recalls anti-semitic imagery of Jewish influence. The tentacles in a 1981 image called “Our old Friend to the Octopus” stem from an old man’s face. He has a large bulbous nose and is strangling several labeled figures like “Comedy” and “Tragedy”. Behind him is a label of “Jerusalem”. Like “The Government of California”, “Our old Friend to the Octopus” depicts the caricature as a nefarious controller. However, Saul’s critique is pointing to clear political figures and naming them as the nefarious controllers. He is carefully depicting the systematized abuses of political powers.

Can we critique a figure like Martin Luther King Jr.? Saul unabashedly says yes. For Saul, nothing is above reproach and the system is on trial. He is telling a story, one in which the abnormal psychology of America is exposed. In depicting Martin Luther King Jr as an angelic octopus whose tentacles mete out “clean” syphilis a year after his assassination, Saul is pointing to the abuses of Martin Luther King’s legacy. The figure is held up as a mythically vaunted and unassailable character in American history. This construction is largely due to Reagan’s appropriation of King. A 2017 analysis by the Boston Review of MLK Day uncovered a letter Reagan had written to the Republican Governor of New Hampshire: His new position, Reagan explained in the letter, was based “on an image [of King], not reality.” 14 Reagan’s support for the federal King holiday, in other words, had nothing to do with his personal views of the civil rights leader. Instead the holiday provided Reagan with political pretext to silence the mounting criticism of his positions on civil rights. 15

In “The Government of California” we see Saul’s multilayered treatment of these two figures. Reagan used the idea of King, pushing a false narrative of a Black deity who argued for a “colorblind society”. All the while, intending for this ameliorative and purely symbolic announcement to pave the way for further exploitation of Black communities. Martin Luther King Jr’s more radical speeches are pushed asunder, to make way for toothless reiterations of “I Have a Dream” speeches, which promote a non-radical agenda. A mortal is made saint, and by his sainthood, per Saul’s depiction, Reagan quite literally fucks the Black community.

A recent article by Chris Cutrone in the leftist periodical, The Platypus Review, gives us language and context to parse Saul’s abnormal psychology:

capitalism appears as various kinds of cancer cells running rampant at the expense of the social body; whether of underclass criminals, voracious middle classes, plutocratic capitalists, or wild “populist” [or even “fascist”] masses, all of whom must be tampered down if not eliminated entirely in order to restore the balanced health of the system. But capitalism does not want to be healthy in the sense of return to homeostasis, but wants to overcome itself… 16

It is within the unhealthy cancer cells running rampant that Saul situates his work. He culls from the mentality of public opinion and projects the perspective through his own deft hand. The state in which the human figure is projected onto Saul’s canvas is akin to the “suprapersonal” level Brian Massumi discusses with respect to Deleuze and Guattari

Studio Project

Hotel de las Aletas

Fall 2018, Studio 5, Prof. Anders Nereim.

Software Revit, Photoshop

Images

perspective

The earliest recorded tribes that lived on the coastal region of Peru are the Mochu and Nazca. Though few traces are left, archaeologists have been able to establish that their disappearance was likely due to the effects of El Niño, a weather phenomenon that has profoundly affected Peru for thousands of years. Today Lima, Peru faces unique challenges in the tourist industry as a result of climate change and globalism. This studio required us to confront these issues in designing a mid-range luxury hotel in Lima’s most vulnerable neighborhood of La Punta. Located on an isthmus flanked by the Pacific Ocean, La Punta already encounters flash floods and tsunami warnings at an alarming rate. Coupled with increasing economic anxiety with respect to tourism, local culture and history, this site poses a complex series of questions.

Hotel de Las Aletas was conceived as a project that would reinvigorate the hotel and tourist industry in Lima. Imagined as an urban space, the divisions between tourist and local are blurred. Daily encounters and transactions are presented as part and parcel of the contemporary travel encounter. Influenced by formative Peruvian design history, the structure is modeled in the rectangular grid of Andean archaeological sites. Its spatial dominance subverts the colonial plaza by placing it in dialog with the large open gathering spaces of the Incan landscape and responds to the scale of the Peruvian military museum located in the same neighborhood, while maintaining a reserved height with respect to the height of the surrounding area.

The roof slopes on the western interior wall. The slope is a welcoming gesture, inviting visitors to sit on the gentlest part of the slope or enter through the aperture. The slope also allows for the collection of water during the rainier seasons. Located in the cavernous sublevel is a large cistern which collects grey water for use in irrigation during the drier seasons. A recessed truss helps elevate the titular “aletas”. They are pushed in and extend out towards three load-bearing walls which appear to effortlessly support the weight of the curved roof. Elevated just 25’ above sea level, the top of the plaza can also be a place of refuge during floods and storms while forming an island accessible by boat when the site becomes permanently inundated. From the axis of the rectangle to the overhang of the coplanar roof and floor, every effort is made to ensure that the structure maximizes a passive, sustainable, and welcoming space.

Studio Project

The City in the Sea

Spring 2017, Studio 2, Visiting Artist Ang Li.

Software Rhino, Grasshopper, Illustrator, Photoshop, InDesign

Images

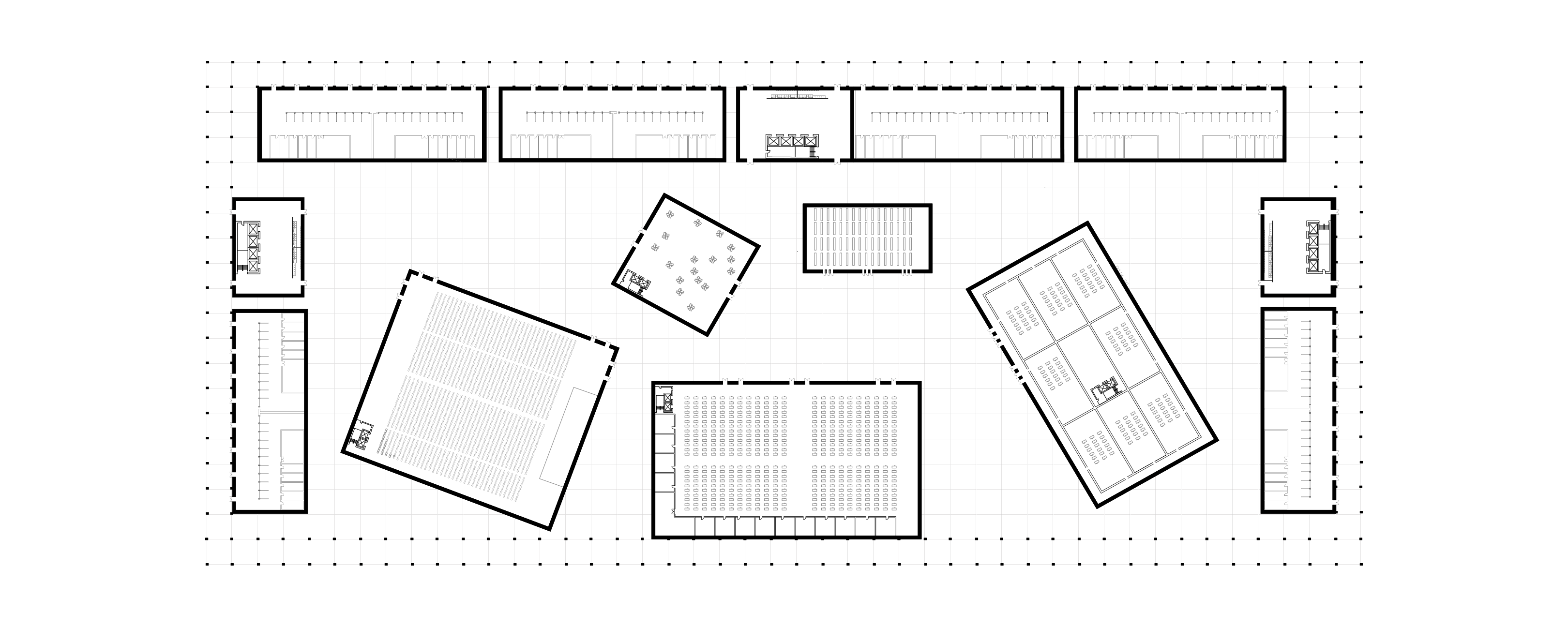

axon

At what point does a building become a ruin? How do we accommodate obsolescence? Chicago, a city famous for its collection of modernist towers and site plans, must constantly make way for the needs and demands of contemporary society, or it faces its own demise. The Lakeside Building at the McCormick Convention Center is one of the city’s poster children of this crisis of capitalism. The behemoth sits at 800,000 sqft. Though large by many standards, this is quite small by contemporary convention center standards. Too big to die, too small to be thrive.

Inspired by Edgar Allan Poe’s poem, The City in the Sea, this project unfurled in two ways. The first strategy was to reconsider a program that would suit the urban scale of the site. This was achieved by relocating Chicago’s financially-burdened City Hall to the McCormick center, freeing the valuable Loop offices for income. The second was to consider the apocryphal promises of The City in the Sea. Cities, like buildings, fall to ruin. Their seemingly permanent ornamentation, their robust concrete columns, their endless grids, will become obsolete rubble. The landscape below city hall is comprised of a new ruin garden. Each pillar is a compressed building that has been demolished. The rubble is a reminder to the bureaucratic inhabitants that endings are a constant.

The City in the Sea

Edgar Allan Poe, 1831.

Lo! Death has reared himself a throne

In a strange city lying alone

Far down within the dim West,

Where the good and the bad and the worst and the best

Have gone to their eternal rest.

There shrines and palaces and towers

(Time-eaten towers that tremble not!)

Resemble nothing that is ours.

Around, by lifting winds forgot,

Resignedly beneath the sky

The melancholy waters lie.

No rays from the holy heaven come down

On the long night-time of that town;

But light from out the lurid sea

Streams up the turrets silently-

Gleams up the pinnacles far and free-

Up domes- up spires- up kingly halls-

Up fanes- up Babylon-like walls-

Up shadowy long-forgotten bowers

Of sculptured ivy and stone flowers-

Up many and many a marvellous shrine

Whose wreathed friezes intertwine

The viol, the violet, and the vine.

Resignedly beneath the sky

The melancholy waters lie.

So blend the turrets and shadows there

That all seem pendulous in air,

While from a proud tower in the town

Death looks gigantically down.

There open fanes and gaping graves

Yawn level with the luminous waves;

But not the riches there that lie

In each idol's diamond eye-

Not the gaily-jewelled dead

Tempt the waters from their bed;

For no ripples curl, alas!

Along that wilderness of glass-

No swellings tell that winds may be

Upon some far-off happier sea-

No heavings hint that winds have been

On seas less hideously serene.

But lo, a stir is in the air!

The wave- there is a movement there!

As if the towers had thrust aside,

In slightly sinking, the dull tide-

As if their tops had feebly given

A void within the filmy Heaven.

The waves have now a redder glow-

The hours are breathing faint and low-

And when, amid no earthly moans,

Down, down that town shall settle hence,

Hell, rising from a thousand thrones,

Shall do it reverence.